You’re counting that study twice!

Why study grouping breaks meta-analyses (and how OTTO-SR fixes it)

By Christian Cao | February 16, 2026

TL;DR

- Systematic reviews analyze “studies.” But studies can be reported through many different papers/reports. Misidentifying which papers report on the same study can distort the final results.

- Otto can automatically group papers reporting on the same underlying study, saving researchers several hours of challenging work.

- When we ran this algorithm on 100 Cochrane reviews, our algorithm caught and corrected several errors with meaningful changes to the study conclusions.

When performing a systematic review, it’s common to encounter different papers all talking about the same underlying dataset (‘study’).

For example, a single cohort from a trial may be described in a conference abstract, a preprint, a published paper, and a later follow-up analysis.

- If researchers don’t properly group these different papers reporting on the same study, each paper might get analyzed, and the same trial can be counted twice (or more) in the final analysis.

- Alternatively, if researchers incorrectly group different papers as a single study, they can unintentionally exclude eligible studies from downstream analysis.

Both errors distort sample sizes, bias effect estimates, and can meaningfully change conclusions.

Consequently, researchers must carefully identify and group related reports into “study groups” before performing data analysis. This is a tedious and difficult task, and can take hours to days depending on the size and complexity of the review.

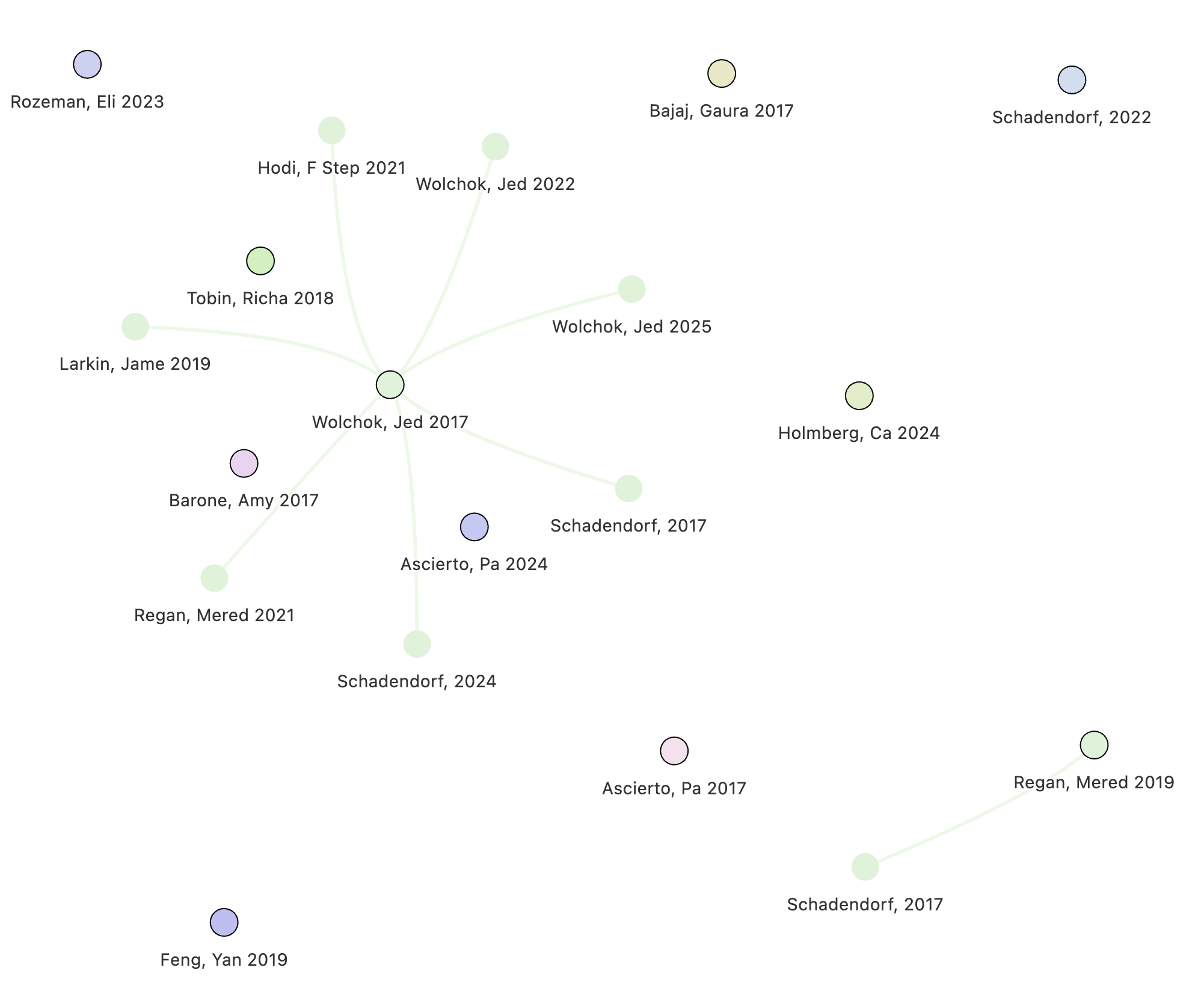

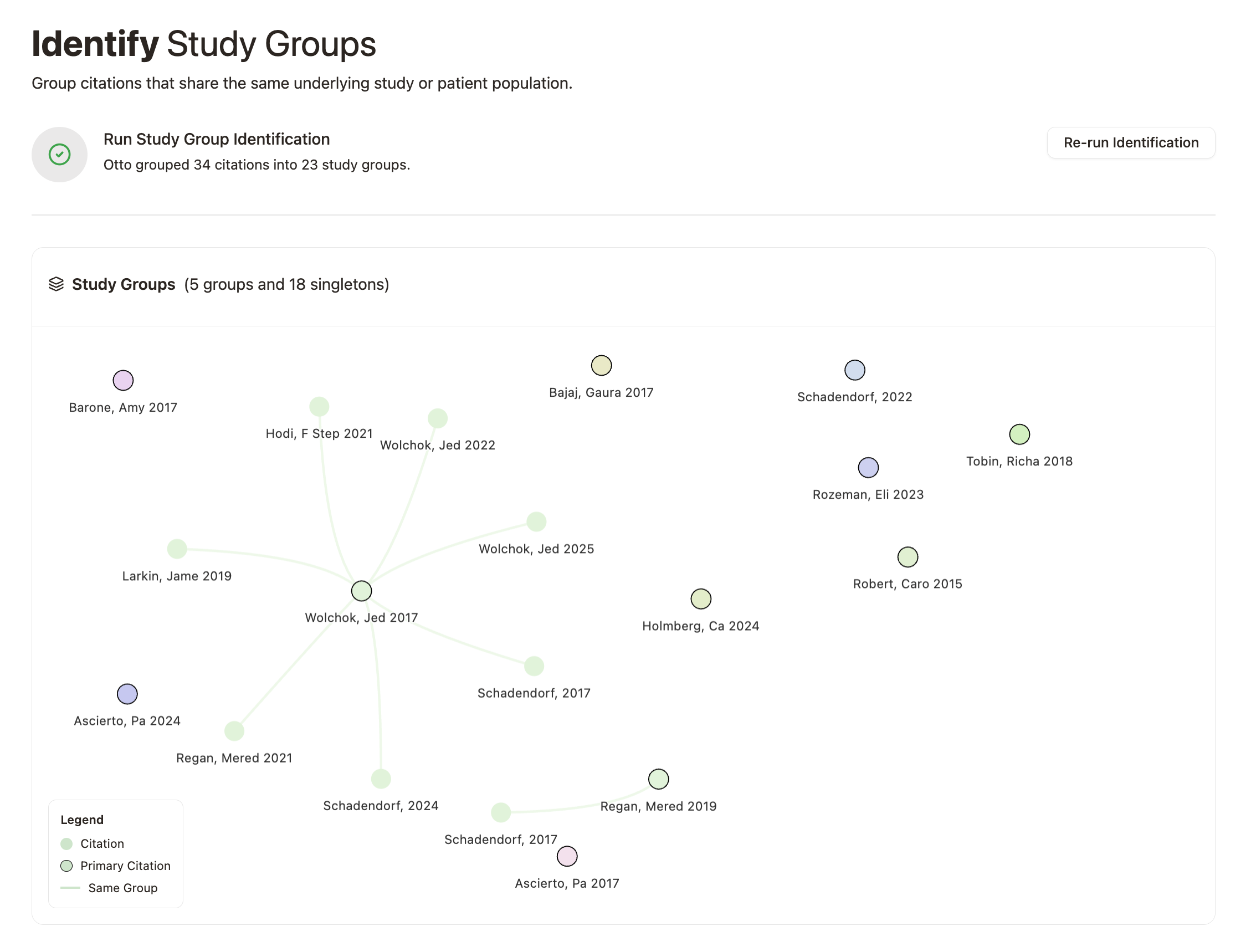

With Otto, we can automatically identify and group these related reports with near-perfect recall and precision.

Study groups in Cochrane Reviews

To benchmark the performance of our algorithm, we analyzed a random sample of 100 Cochrane reviews.

Cochrane reviews represent the best evidence practices available.[1] They have rigorous reporting requirements and authors carefully document how multiple reports are linked to underlying study groups.

However, even in these high-quality reviews, our algorithm may outperform human researchers.

We found that 3% of Cochrane reviews had errors in study grouping that directly impacted final meta-analyses, meaning that either:

- Researchers grouped reports that were not related (false exclusion); or

- Researchers failed to group papers that were related (over-counting)

Let’s explore some examples below!

Hormone therapy for sexual function in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (n = 218 citations)

We identified several errors in the Cochrane review: “Hormone therapy for sexual function in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women” (Lara 2023).

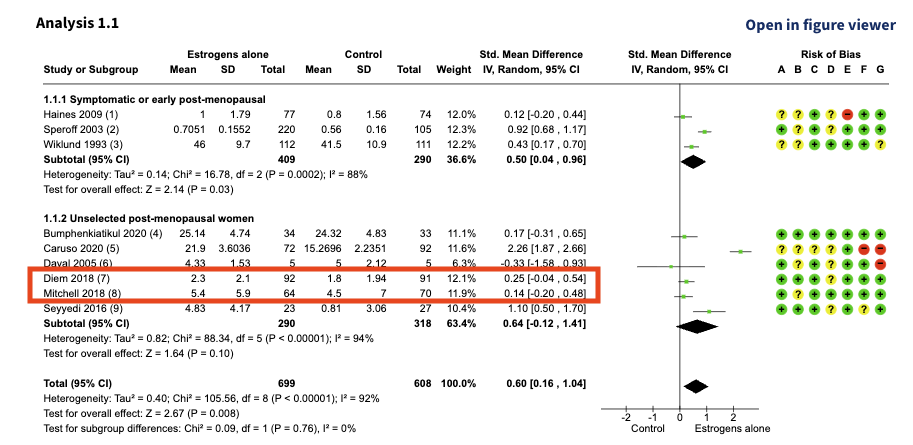

Diem 2018 and Mitchell 2018 are included in the following analysis:

At first glance, Diem 2018 and Mitchell 2018 look like two separate studies. The sample sizes, mean values, and effect estimates are all different.

However, both papers cite the exact same clinical trial: NCT02516202, meaning that they aren’t two independent trials; they’re two reports of the same trial. The difference in values is because each paper reports a different questionnaire (or outcome) measuring a similar concept.

Diem 2018 reports outcomes using the MENQOL scale, while Mitchell 2018 reports outcomes using the FSFI index. Treating them as separate studies double counts their impact.

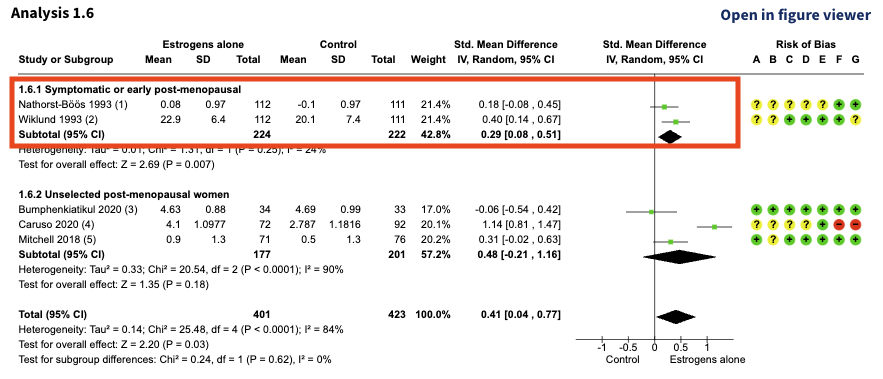

Nathorst-Böös 1993 and Wiklund 1993 were also included in the following analysis:

At first glance, Nathorst-Böös 1993 and Wiklund 1993 also look like two separate studies. The sample sizes are the same, but the mean values and effect estimates are different.

Let’s take a closer look:

| Study Name | Population | Interventions | Outcomes | Sample Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nathorst-Böös 1993 | Postmenopausal women between 45 and 65 years of age requiring hormonal replacement therapy (HRT). Recruited from 15 centers located in different parts of Sweden. | Estradiol therapy (Estraderm 50 ug/24 h) (E) or Placebo (P) | “A Swedish version of ‘McCoy’s Sex Scale Questionnaire’” with nine items | 242 women were randomised; n = 112 E; 111 P. 3 participants “who did not fulfil the inclusion criteria were excluded from the analysis” |

| Wiklund 1993 | Postmenopausal women between 45 and 65 years old requiring hormone replacement therapy for climacteric symptoms. Women from 15 centers volunteered for the study. | Transdermal estradiol therapy, 50 ug/24 hours, or placebo given as patches twice a week | McCoy Sex scale. “An abbreviated form with nine items was used” | 242 women were randomized; n = 112 E; 111 P. “Three of these were excluded from the analysis as protocol violators” (not fulfilling the inclusion criteria?) |

These two studies seem suspiciously similar. They have identical populations, interventions, outcomes, and study characteristics.

So why are the reported means different?

- Nathorst-Böös 1993 analyzed a single question from the McCoy scale (Question 8).

- Wiklund 1993 analyzed the aggregate of three questions from the scale.

In other words, the outcome definitions differ, but the same instrument was used. However, both reports were incorrectly treated as independent studies in the meta-analysis. Again, the same trial was counted twice.

Interventions for preventing posterior capsule opacification (n = 322 citations)

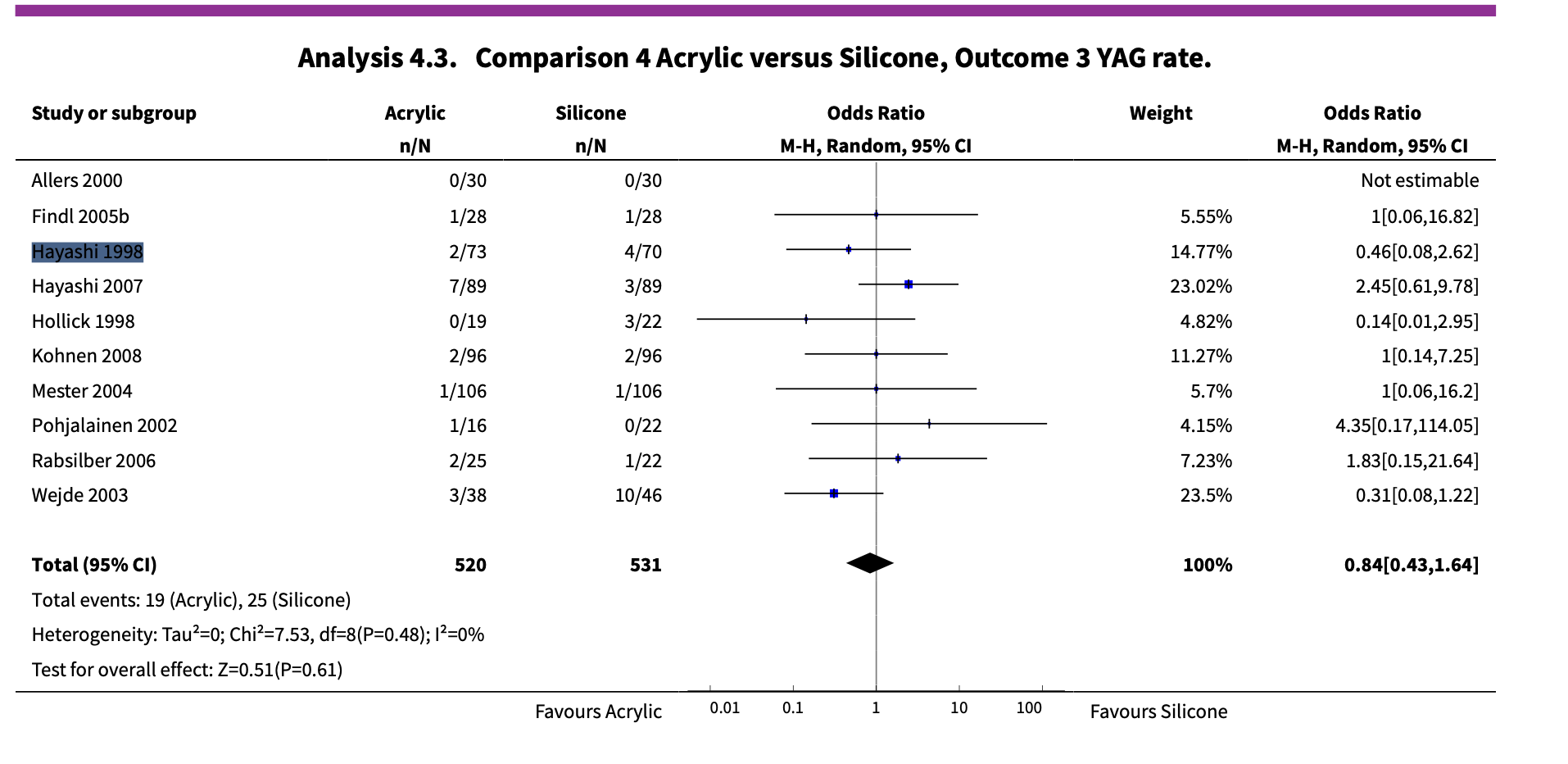

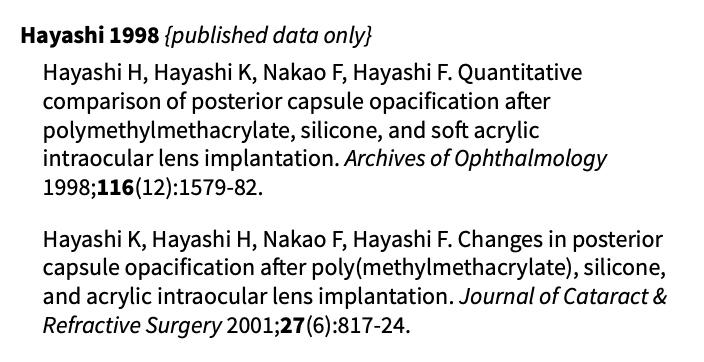

In the Cochrane review: “Interventions for preventing posterior capsule opacification” (Findl 2010), Hayashi 1998 was used in the following analysis:

The authors group the Hayashi 1998 study from two papers:

- Hayashi’s original 1998 paper “Quantitative comparison of posterior capsule opacification after polymethylmethacrylate, silicone, and soft acrylic intraocular lens implantation”; and,

- Hayashi’s 2001 paper “Changes in posterior capsule opacification after poly(methyl methacrylate), silicone, and acrylic intraocular lens implantation”.

At first glance, the studies seem to be the same, sharing similar author lists and titles—maybe it’s a follow-up study?

The reporting in Hayashi 1998 also lacks detail; the methods don’t provide a clear explanation for where the patients came from.

However, upon closer inspection, these are not two reports of the same patient cohort; they are distinct studies.

Our system caught a small nuance buried in the discussion section of Hayashi 2001. Here, Hayashi 2001 cited Hayashi 1998 as a “previous study” that was performed retrospectively in their discussion. Meanwhile, Hayashi 2001 writes about a prospective cohort. Hayashi 1998 and Hayashi 2001 are actually two distinct studies that analyzed separate patient cohorts.

Unfortunately, the authors only extract outcome data from the Hayashi 1998 paper; data from Hayashi 2001 was not considered in any meta-analysis. This means that the Cochrane review had incorrectly excluded an eligible study in their meta-analysis.

Mindfulness-enhanced parenting programmes for improving the psychosocial outcomes of children (0 to 18 years) and their parents (n = 22 citations)

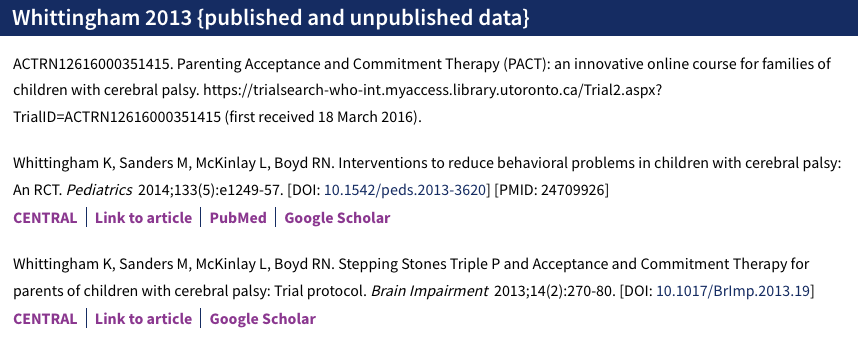

In the Cochrane review: “Mindfulness-enhanced parenting programmes for improving the psychosocial outcomes of children (0 to 18 years) and their parents” (Featherston 2024), Whittingham 2013 was grouped as follows:

Let’s take a closer look at each study within the study group:

| Study Name | Description | Population | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTRN12616000351415 | Represents a (now published, May 2025) trial registration for an RCT | 66 parents with a child (2-6 years old) with Cerebral Palsy | Parenting Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT) |

| Whittingham 2013 | RCT Protocol | 110 parents of children (aged between 2 and 12 years at point of recruitment) with Cerebral Palsy | Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP) +/- ACT |

| Whittingham 2014 | Published data, directly cites Whittingham 2013 as the protocol | 67 parents of children with Cerebral Palsy | Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP) +/- ACT |

Here, the Cochrane authors incorrectly grouped the ACTRN12616000351415 trial with Whittingham 2013/2014, despite these representing distinct trials with different populations and interventions.

Although this error did not materially affect the review’s conclusions at the time (ACTRN trial data was not available), it risks incorrectly excluding an eligible study in future review updates.

OTTO-SR’s mission

The errors above weren’t made by careless reviewers; they were made by some of the best in the field, working within the most rigorous framework we have.

Our algorithm catches subtle distinctions: a “previous study” buried in a discussion section, a shared trial registration hidden behind different author lists, or the same patients concealed by different outcome measures.

If you’d like to see how Otto handles related reports in your reviews, get in touch. And if you’re interested in shaping the future of evidence synthesis, reach out to join us here!